If you’ve ever watched "Die Schweizermacher", the 1978 Swiss film about naturalization, one scene probably stuck with you. Two officials. Clipboards in hand. Measuring “Swissness” as if it were a checklist.

Back then, it felt exaggerated. Almost satirical. Fast forward to 2026, and the uncomfortable truth is this: the film no longer feels like fiction.

The Swiss citizenship interview remains one of the most discussed, misunderstood, and occasionally controversial steps in the naturalization process. While federal law clearly defines who may become Swiss, the interview itself is still shaped by local practices that can vary wildly from one municipality to the next.

Sometimes, those differences border on the absurd.

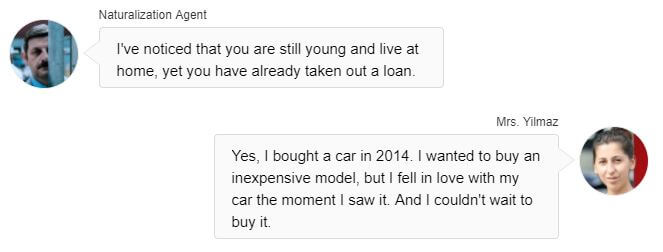

A Case That Refused to Go Away

Back in 2017, a naturalization case from the town of Buchs made international headlines. A young woman, born and raised in Switzerland, fluent in Swiss German, educated in the local school system, was denied Swiss citizenship.

Her name was Mrs. Yilmaz.

The reason was not criminal history or lack of integration. Instead, it was a series of interview answers that were deemed insufficient. She could not recall all emergency numbers correctly. She did not belong to a local club. She preferred large grocery stores over small neighborhood shops.

Her idea of “typically Swiss” leaned toward the Alps and chocolate rather than Schwingen or Hornussen.

When asked what Swiss citizenship would mean to her, she answered honestly: not much would change, except the right to vote.

That answer alone unsettled the interviewers.

At the time, many readers wrote to me saying the interview transcript felt invasive, even intimidating. The core question lingered: how can someone who lives Swiss daily life still fail a Swiss citizenship interview?

Nine years later, the question has not lost relevance.

Cow Coats, Zoo Animals, and Other Unexpected Topics

Recent reporting by the Zürichsee-Zeitung suggests that the Swiss citizenship interview still includes questions that go far beyond what most residents would reasonably know.

Using freedom of information requests, the newspaper collected question lists from 30 municipalities in the canton of Schwyz. Some of the findings are eyebrow-raising.

Swiss citizenship applicants may be asked:

- What color most cows have in Muotathal

- Which animals are kept at the outdoor animal park in Goldau, and whether certain species share an enclosure

- Whether more people should immigrate to Switzerland

- What they think about girls having to attend swimming lessons

In one municipality, applicants were reportedly asked which passport they would keep if they had to choose, despite Switzerland explicitly allowing dual citizenship.

To be fair, not every question is actually used in interviews. Some municipal officials later clarified that certain questions exist on paper but are never asked. Still, the fact that they appear on official lists raises an uncomfortable issue.

If these questions are not meant to be asked, why are they there at all?

What the Law Actually Says

Swiss federal law is remarkably clear on this point. There is one civic knowledge test that applicants must pass. Beyond that, naturalization is an administrative act, not a personality assessment - and definitely not a quiz show.

This was reinforced by the Federal Supreme Court in 2019. The court ruled against the citizenship practices of the city of Schwyz after an Italian resident, who had lived in Switzerland for 30 years, was denied citizenship partly because he did not know that bears and wolves were housed together in the local zoo.

The ruling was explicit: Naturalization is not a professional exam. Interview questions must not go beyond what can reasonably be expected of an ordinary resident of the community.

Barbara von Rütte, a legal scholar at the University of Basel, summarized it even more plainly: "Naturalization is neither a privilege nor a political favor. It is an administrative process. Question lists must not turn into a second, disguised knowledge test."

And yet, in practice, some municipalities continue to rely on exactly such lists.

Why Local Discretion Still Exists

To understand why the Swiss citizenship interview remains inconsistent, you need to understand Switzerland itself.

Citizenship is federal, cantonal, and communal. While the Confederation sets the framework, municipalities still play a key role in assessing integration. For small towns, the interview is often seen as a conversation rather than a checklist.

An administrative employee in Rothenthurm, a municipality of around 2,500 residents, explained it bluntly: if the interview does not go well, they may fall back on the question list.

That sentence says a lot.

The interview is supposed to confirm integration, but not define it. In cases when interviewers feel uncertain, they use question lists and go into trivia mode.

Swiss Citizenship Is a Bottom-Up Process

Another reason the Swiss citizenship interview feels so unpredictable is that Swiss citizenship itself is built from the bottom up.

You don’t become Swiss first. You become a citizen of your municipality, then your canton, and only at the very end of Switzerland as a whole.

Each level has the power to assess integration. And while federal law defines the framework, municipalities are given wide discretion in how they evaluate applicants. That’s where interviews, question lists, and local expectations enter the picture.

In practical terms, this means that two applicants with identical backgrounds can face very different interviews depending on where they live. A municipality with a long tradition of naturalizations may treat the interview as a conversation. A smaller commune may rely heavily on written question lists or local trivia.

This structure helps explain why questions about cows, zoos, or village customs still surface, even though courts have repeatedly warned against turning interviews into disguised knowledge tests.

The Human Side of the Interview

Several "Newly Swissed" readers who went through the Swiss citizenship interview have shared their experiences with me over the years.

One applicant recalled being asked where to buy the best bread in town. She answered honestly and named a supermarket. The interviewer raised an eyebrow and asked why not the local bakery.

Another remembered being quizzed on recycling rules that had changed twice since she moved to the municipality. She knew the basics but not the exact container colors.

A third applicant described the language test as the most nerve-wracking part. Not because he lacked vocabulary, but because speaking dialect in a formal interview felt unnatural. What helped him most, he said, was casual conversation with neighbors at the local café.

For me, all of these stories highlight something important. It's that "integration" cannot be measured with trick questions. It shows up in everyday life, often quietly.

What Applicants Should Actually Prepare For

Despite the headlines, most Swiss citizenship interviews are fair and respectful. Still, preparation matters.

Applicants should be comfortable discussing:

- Swiss geography at a basic level, but including the names of local hills, creeks, etc.

- The Swiss political system and federal structure

- Local traditions and public life

- Daily norms such as recycling, public transport, and civic participation

Your language skills do matter, but you don’t have to sound perfect. The focus is on whether you can get your point across in daily life.

But be aware that by the time you sit down for a Swiss citizenship interview, most decisions have already been made on paper.

You must hold a Swiss C permit, have lived in Switzerland lawfully for at least ten years, and meet strict financial and legal criteria. Outstanding debts, unpaid taxes, or welfare reliance in recent years can end an application before an interview is scheduled.

In other words, the interview is not meant to determine whether someone deserves citizenship in principle. It is meant to confirm integration that should already be visible in everyday life.

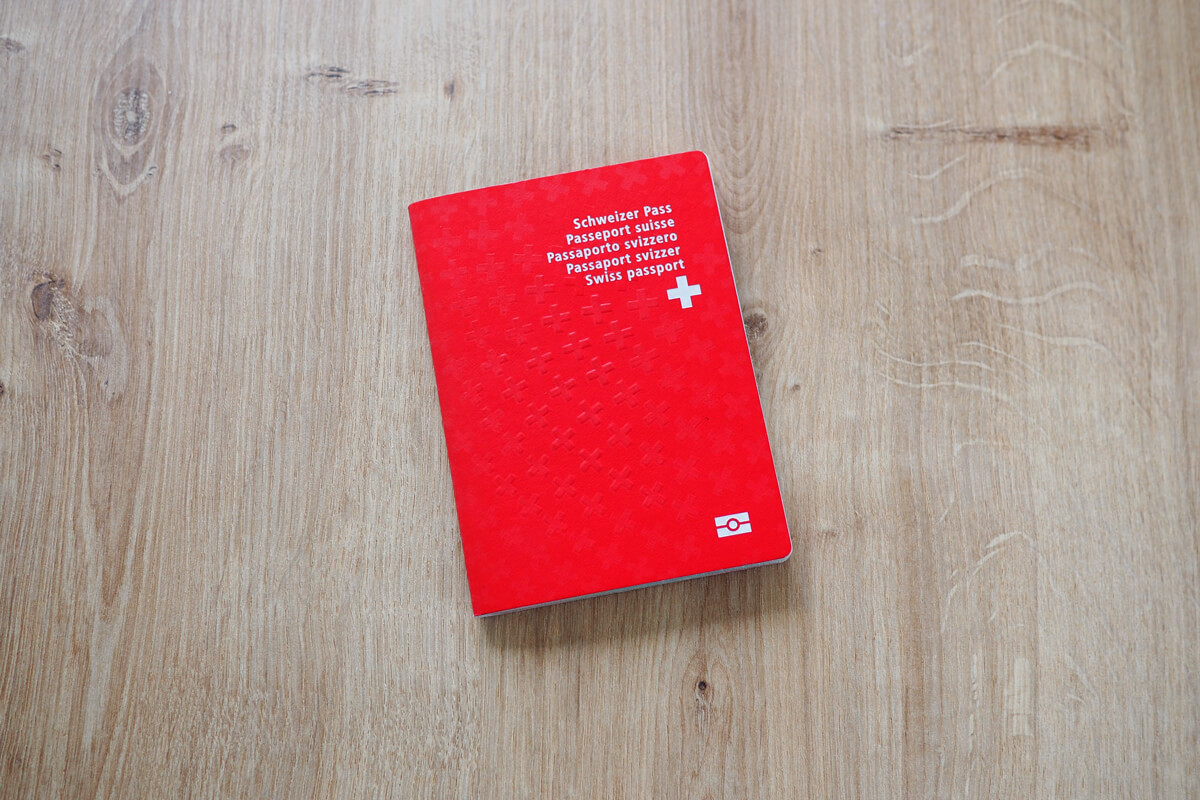

If you are preparing for the process, it also helps to understand what comes after a successful interview. Once citizenship is granted, the next practical step is applying for your passport.

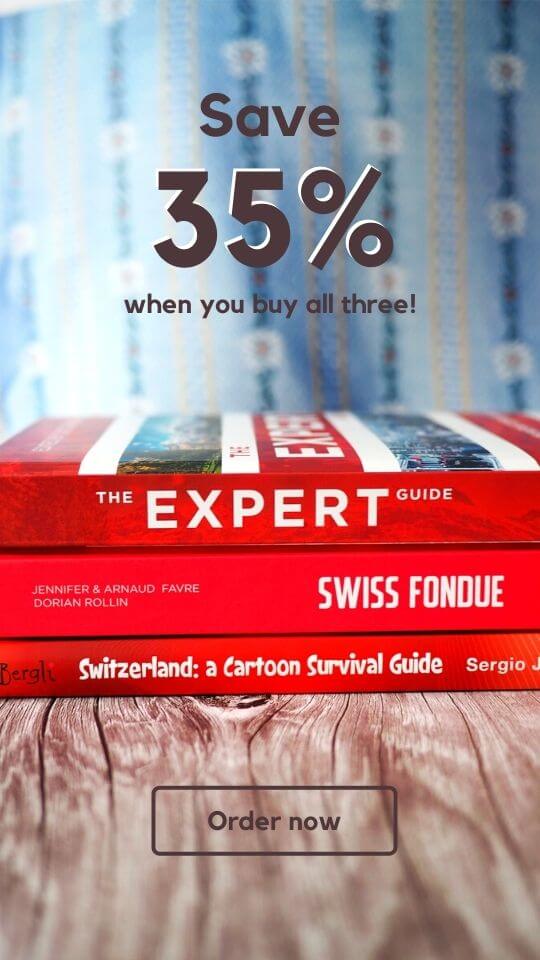

We recently published a comprehensive Swiss passport application guide for 2026, covering eligibility, documents, costs, and new security features. It is worth bookmarking early so you are not scrambling later...

From Interview to Passport

Ironically, the passport itself is the least subjective part of the entire process. Once you are Swiss, the passport application follows a standardized routine: fixed fees, predictable timelines, efficient biometric appointments.

There are no questions about cows, zoos, or shopping habits. That contrast alone should give policymakers pause. The good news is that the system does appear to be adjusting, yet slowly. Several municipalities have begun revising their question lists, while others are questioning whether such lists are needed at all.

Media scrutiny and court rulings have had an effect, even if progress remains uneven. What is still required is a cultural shift: the Swiss citizenship interview works best as a conversation about integration, not as a test of local trivia.

Are you Ready to Become Newly Swissed?

Switzerland cannot expect immigrants to live a textbook version of Swiss life. Many Swiss citizens themselves would fail some of the questions currently floating around in municipal binders.

What Switzerland can reasonably expect is respect for the law, basic civic knowledge, language skills, and a willingness to participate in society.

When the Swiss citizenship interview reflects that reality, it does exactly what it is meant to do. It confirms belonging, rather than policing it.

And maybe, just maybe, Die Schweizermacher can finally return to the category of historical satire where it belongs.

Even me – not Suisse – would not be excited to issue the Swiss passport for her (interviewee). She has definately lack of knowledge and lack of interest of he “own” country.

If you lived in Switzerland your entire life, speak the language, know the country – they you probably ALSO know the answers that the interviewers are looking for. If she really wanted citizenship it seems she probably knew the “best” answers to give to the questioners to gain points – but instead answered truthfully. Is truthfulness a bad thing? Some Swiss people seem quite effective at delivering large amounts of condescension and judgment.

But overall this line of questioning is ridiculous. When the next European war breaks out I think the questioner might be on the other side of the table – let’s see how quickly HE answers the questions with the “best” answer or if he would risk being truthful.