I had a déjà-vu of my student days in Lausanne when I entered the IBM Research campus near Zürich.

While it reminds of a university campus, this is neither a university nor a multi-national corporation. IBM Research has just the perfect blend of a laid-back yet solution driven attitude.

This year marks sixty years of IBM’s research funding in Switzerland. Smitten by the tranquil environment this alpine country offers and an environment in which talent scientists and engineers are in constant supply, it was not surprising for IBM to choose Zürich for establishing the first research laboratory outside of United States.

(At that time, IBM had manufacturing facilities in 14 countries and sales offices in 80.)

A New Industrial Pattern in Switzerland

Ambros Speiser, a Swiss electrical engineer, was entrusted with the task of building a research team. The requirement was unique, as his European team was to collaborate with the United States and the rest of the international scientific community.

It was neither the availability of building space nor the shortage of brilliant scientists and engineers from ETH Zurich and other top universities that posed a challenge to Speiser.

Instead, Speiser had to create an industrial laboratory, separate from a production facility - a concept that did not exist at that time in Switzerland.

After having rented out a small facility in Adliswil, Speiser met with an intellectual to discuss his business challenge: How to prevent the operations of the lab to be shut down? How to evolve his R&D centre over time? And how to avoid becoming yet another repetitive lab facility?

In 1958, all the pieces fell in place for Speiser and his brilliantly set up research team. In agreement with IBM headquarters, the Zürich lab changed its focus from electronics to physics. Emphasis was given to the field of solid-state which provided the basis for future electronic devices.

From Adliswil to Rüschlikon

With a renewed sense of purpose, the Zürich lab expanded. It was to house a new mathematics department, in addition to the electrical engineering and physics labs.

The Adliswil facility was modest in space, and Speiser had to find another site to accommodate his expanding faculty. So in 1963, a new lab was inaugurated on a 10-acre site in nearby Rüschlikon. The move to the new campus was well thought out, making sure that there would be enough room for future expansions.

Check out this rare video from the 1963 inauguration:

Home to four Nobel Laureates

Heinrich Rohrer, Gerd Binnig, Karl Alex Müller and Georg Bednorz are some of the famous names in the world of physics.

They all worked at the IBM Zurich Research Laboratory and were renowned for their research, inventions, discoveries and publications. All of their hard work was recognized when they went on to win Nobel Prizes in two consecutive years in 1986 and 1987.

This remains the crowning glory for this sixty-year old research lab in Switzerland. And it is just a matter of time before other names are added to this illustrious list...

What is IBM Zurich currently working on?

How about these for starters?

- The world's first hot water cooled 64-bit micro server capable of processing Big Bang's enormous data;

- Noise free labs built to exclude even the tiniest bit of disturbances or temperature fluctuations;

- Multi-level phase change memory for a new generation of communication devices;

- Reduction of CO2 emissions in data centers;

- Conversational leaves to receive data in areas with no human access;

- Next generation quantum computer;

- Innovative cloud-based technology to protect personal data online against cyber security threats.

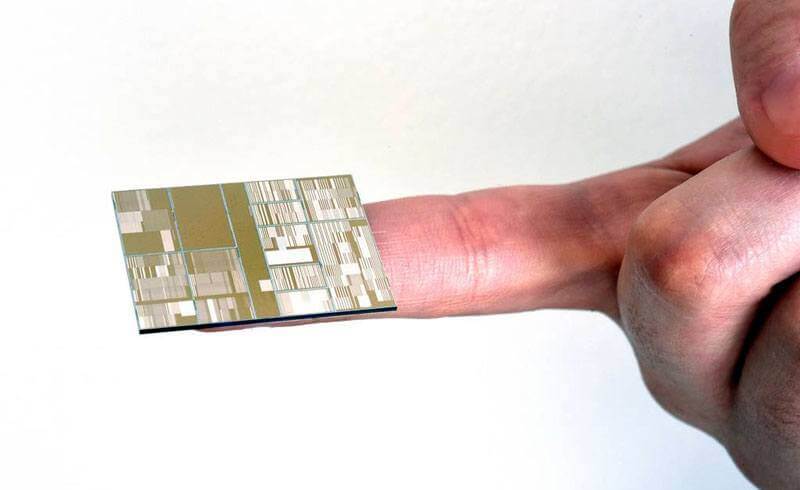

Or take this: A chip with 20+ billion transistors, bringing huge improvements over today’s most advanced technology:

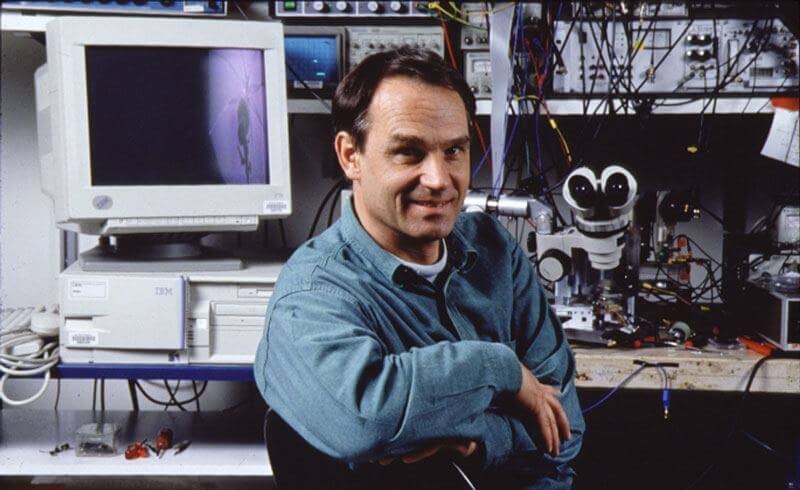

The scanning tunneling microscope (STM), which was invented by Gerd Binning and Heinrich Rohrer, is a cornerstone innovation of the IBM Research Laboratory in Zürich. This technology has allowed scientists to image individual atoms on a surface, helping to push the limits in the semiconductor industry.

Here is Nobel laureate Gerd Binnig in his laboratory in the late 1990's:

Today, STM helps the lab stay relevant by meeting the increasing demands in the area of atomic, molecular and optical studies.

In a partnership with ETH Zurich and EMPA, a state of the art nanotechnology facility was established in 2011. It was aptly named the Binning and Rohrer Nanotechnology Centre.

A final note

Terms like research, laboratory, physics, computing and technology always come with a hint of sophistication, difficulty, sans fun and mundanity.

However, one must visit the lab and interact with the talented scientists, engineers and other administrative staff to feel the sense of purpose as to why they conduct research and develop products.

"It is easy to create complicated systems, but difficult to simplify."

Those were the words from an IBM researcher over a chat we had during lunch. He went on to talk about his life outside the laboratory and shared glimpses of his many hang-gliding experiences from around the world.

As I left the research lab, I wondered how a layman might understand what this league of scientists and engineers actually do. Well, one cannot explain the intricacies of how things work while isolating the finer details. But one can appreciate their work if we can take a step back and look at the way our lives have evolved.

Now, that would be a start!

(Most photographs courtesy of IBM Research - Zurich. Unauthorized use not permitted.)

Conversational leaves? Interesting concept but why receive data where there are not humans? perhaps send data from where no humans exist? To be a conversation we need to send as well as receive, I suppose. Is it that a difficult problem in these days with remote sensing capabilities?

Hi Bala, the idea is that the leaves have sensors which can report if the ground temperature is getting too hot, too dry and potentially a fire could start. The naming is a bit misleading.